Micro-ambition, or “the passionate pursuit of short-term goals” is generally attributed to Tim Minchin, an Australian comedian and somewhat of a renaissance man, who advocated for the term in a 2013 commencement address (which offers other truisms that I passionately endorse, including, “There is an inverse correlation between depression and exercise. Do it. Run, my beautiful intellectuals, run”).

Whereas macro-ambition refers to the passionate pursuit of The Dream, micro-ambition refers to the work in front of you. Macro-ambition sometimes works for those with A Dream, but it doesn’t always lead to success, and the cost of pushing achievement into an indeterminate future can be high.*

That’s why while most of our clients procure our services in the pursuit of macro-ambition, we try to structure our offerings according to short-term goals and the work that needs to be done today. This sort of micro-ambition too neatly dovetails with the uniquely American dedication to life-hacking productivity, but micro-ambition does not advocate for productivity for its own sake. After all, there’s nothing either particularly ambitious or necessarily fulfilling about simply being “productive.”

Rather, we offer micro-ambitious services that we’ve typically described as “strategic.” For example, for an author working on a first draft of a memoir, we offer strategic prompts soliciting tiny stories that contribute to the memoir’s theme. Or, for an author testing out curriculum guidelines for inclusion in a guidebook, we help create smaller strategic publications to determine reader engagement and guideline efficacy.

Strategy has become too encompassing a word, though, probably because it has been just about fully pushed into the land of useless jargon (from which words rarely return). Micro-ambition, though at first glance just as useless, captures for the moment the very small achievements that can elicit the engaged work that ultimately adds up to A Dream, even if it’s not the dream the author first had in mind.

*Minchin’s existential takedown of the lifetime pursuit of A Dream: “[I]t’ll take you most of your life to achieve, so by the time you get to it and are staring into the abyss of the meaninglessness of your achievement, you’ll be almost dead so it won’t matter.”

Although the push for efficient productivity seems to be waning, the desire to discover a new app, method, or model to spur a project to completion will always wax. We’ve read lots of books and implemented lots of models, and—lucky for you!—we’ve discovered the secret.

The best way to finish a project is also the simplest: First, define your audience, your message, and your method. Then, create a shared calendar or timeline. Third, stick to it.

Project completion is often obstructed by too many people knowing too little. This is a variation on the old too-many-cooks-in-the-kitchen trope. Typically, the issue is not that there are too many bodies working over one stove, it’s that few of these bodies can be considered “cooks,” and none of them are working with a recipe.

Do better by designating yourself the chef and creating a recipe that anyone can follow. In terms of a project, this means straightforwardly defining—but then recording and sharing—your specific audience, your message to them, and the most efficient, most welcome form of delivery.

For a nonprofit communications project, this might mean that after you determine a fundraising goal, you identify your supporters most likely to contribute to that goal, and then develop a social media-based fundraising campaign and marketing collateral that will reach and reward them. For a coauthored book project, this might mean that after you determine a self-help-book goal, you determine readers most likely to be moved by your message, and then develop an organization scheme that will reach and resonate with them.

If you want to finish a project with a minimum of detours, it’s necessary to do this relatively low-effort work. If also necessary to create—and to record and share—a calendar or timeline.

We’ve frequently discussed calendars in terms of editorial calendars—and those are great. However, our nonprofit and book-making clients are often overwhelmed by the inputs required by the editorial-calendar format. For these clients—and for you—a calendar can be as simple as an auto-formatted Google Sheet that breaks down the calendar you’re already using in a more granular, more accountability-fostering way.

Ultimately, project completion requires getting back to basics: Defining and sharing your audience, your message, and your method ensures everyone is on the same page. Putting together a project calendar will provoke participation, and sticking to it promises completion.

RescueTime, for example, has a “forever-free” version offers tracking and reporting and thus fosters online accountability on par with iPhone’s hate-loved screen-time summary. But it also enables users to set goals. If you spend a lot of time on email, you can find out how much is too much, and you can set a goal to stop.

Related to RescueTime: a Chrome extension. The bare-bones web time-tracker is good for people (not me/me) who like having a tiny clock ticking dictatorially away in their browser. The counting may provoke complicated emotions—anxiety, annoyance, rage—but some people like the fight-or-flight mindset it triggers

Followup is a high-maintenance-to-be-low-maintenance app, but, alas, it doesn’t have a forever-free version. What it does have (for a steep $18.00/month), is email tracking capability. You’ll spend more time “processing” emails, but less time remembering when to respond to and then actually responding to them. If your work depends on networking, on bids and proposals, or on project-managed teams, Followup is a more powerful, more comprehensive, and far more active and participatory Gmail-nudge.

While I frequently wonder why productivity apps are even necessary—why do I sabotage my productivity when I definitely don’t want to (and when my time is so short)—until I answer that question in a way that permanently changes my behavior, I’m relying on apps like these.

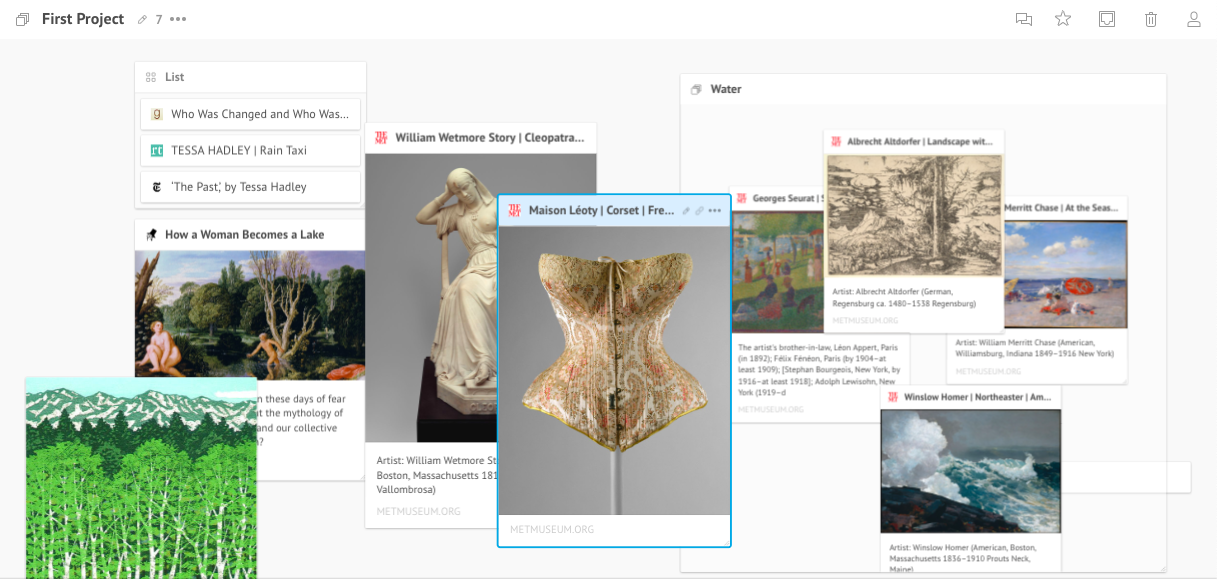

For example, if you’re working on a speech or a presentation, you could fill your canvas with thumbnail links of your subject matter. You could then attach other links (like particularly apt comments or tweets or relevant op-eds), other images (like a grabs from previous presentations), and text-based responses (like lists of audience questions) onto the images themselves.

This is helpful, and in some surprisingly deep ways. If you’re looking to repurpose or refresh a project, Webjets provides an engaging format through which to envision your work. If you’re looking to gain insights or access points into stubborn questions, Webjets can help you reorganize your files in new ways (like lists, cards, folders, or mind maps). If you’re looking to collaborate with a partner or a team, Webjets lets you share your screen for pretty efficient (and frankly very fun) collaborative brainstorming sessions.

Did I need a new way to envision and brainstorm new projects? In fact, yes! My old way of brainstorming cannot even be called a “way”; it’s certainly not efficient; and it’s not at all conducive to structured collaboration. As we work on bigger, more collaborative projects at MWS, Webjets offers a narrative snapshot that is more comprehensive and more dynamic than a linear or written description.

The question of whether or not Webjets aids productivity is harder to answer. On the one hand, it will undoubtedly add to the bottomline of time spent brainstorming and collaborating. On the other hand, if it means the end result is a smarter and more creative project, then I’ll happily take it. Have you used Webjets? Tell me more.