Maybe! Launching a project is no joke—it’s a whole lot of work—but for authors, especially authors of niche books or books rich in design elements, Kickstarter can be an excellent move.

Kickstarter offers a home and platform for entrepreneurial authors looking to go their own way, shorten their publication timeline, raise money for quality printing, determine a more accurate count for an initial book run, and establish a place for fans to congregate and show support.

However, Kickstarter should in no way be considered an “easy” route to publication. Its author-driven platform is freeing, but that’s because the author rather than a publishing team takes on fundraising and marketing responsibilities. While that work may be unavoidable (traditional publishers don’t typically invest in niche books with boutique audiences, and they frequently require, implicitly or explicitly, that authors do the heavy lifting in marketing anyways), it can be challenge, especially for the unprepared.

Thinking about launching a Kickstarter campaign? Consider the following:

- Be done: Finish your manuscript. It’s hard (so hard!) to write a book. A work-in-progress not only makes campaign planning impossible, it can also act as a guillotine blade hanging over your head. If it’s difficult to write a book under regular circumstances, it’s nearly fatal to work under the pressure of having to quickly meet backers’ expectations.

- Be prepared: Because you are the project manager for your Kickstarter campaign, you must manage production, value proposition, and fulfillment (in the figurative and practical sense). This is another great reason to build your campaign around a completed book: Rather than managing the book-writing, you can turn your attention to managing a campaign that showcases your book as a beautiful thing poised to do meaningful work out in the world.

- Be wary of incentives: Incentives are great, but they can be an unexpected black hole in terms of time and effort. Offer them, but think hard about what you offer. If it’s not the book itself (and even if it is), every gift must be designed, purchased, organized, fulfilled, packed, and shipped to recipients. In theory, no problem! In reality, that could be 127 XS T-shirts in one of three colors to 123 different addresses; 279 M T-shirts in one of three colors to 279 different addresses; 113 L T-shirts in one of three colors to 109 addresses. And more!

Successful Kickstarter campaigns reward the prepared and persistent. From our perspective, it’s a platform that’s helping to diversify publishing in the form of riskier, niche-ier projects. If you’ve got one, and you’ve got the energy and passion to fuel it, get in there and kickstart it!

- Is not written by the author

- Is written by an expert in the field

- Is about the book’s larger subject and lends credibility to the book and the author

A foreword is an asset to most nonfiction books. Luckily, many nonfiction writers have a network of informed experts (a few of whom probably informed the writer’s source material) who can speak fluently about the writer’s subject matter (and sometimes the writer, too). When to solicit the foreword? Brainstorm possible writers early in the book development process (and when you ask, be sure not to waste anyone’s time).

A preface:

- Is written by the author

- Is only peripherally about the book’s subject

- Is often written to explain how and why an author came to write their book

A preface is often an asset to a nonfiction book. It is pretextual in the sense that it isn’t considered of a piece with the content. It can therefore act as a space where authors, freer to appeal directly to their readers, use candid language to make the book’s content more meaningful and the reading experience more intimate. When to write the preface? Write it when you’re done. In some ways, the preface is a preparatory reflection, and it’s often more efficient to write it while looking back.

An introduction:

- Is also written by the author

- Is typically about the book’s subject

- Is used to supply extra material that augments the book’s subject

An introduction can also be an asset to a nonfiction book. Unlike a preface, an introduction is considered a part of the book. It’s thus a good place for background material that is crucial to consider but that doesn’t fit the book’s narrative arc. When to write an introduction? Write it when you’re done. It’s not always easy to identify whether or not a book needs an introduction. Once the manuscript is complete, it’s easier to determine what has been left out. If the reader will benefit from contextual information, an introduction will help.

An afterword:

- Is not typically written by the author

- Is very like a foreword

- Is used to guide the broader discussion provoked by the book

An afterword is a bit rarer than the other textual frames. Why? Who knows, but maybe out of an assumption that readers will skip out on a book’s last pages? Whatever the reason, an afterword can offer an unexpected and powerful lens through which to view nonfiction (or fiction!) work. When to solicit an afterword? Probably after your book has been released, reprinted, and widely respected. The best afterword discusses a book’s lasting impact on the cultural conversation to which it continues to contribute.

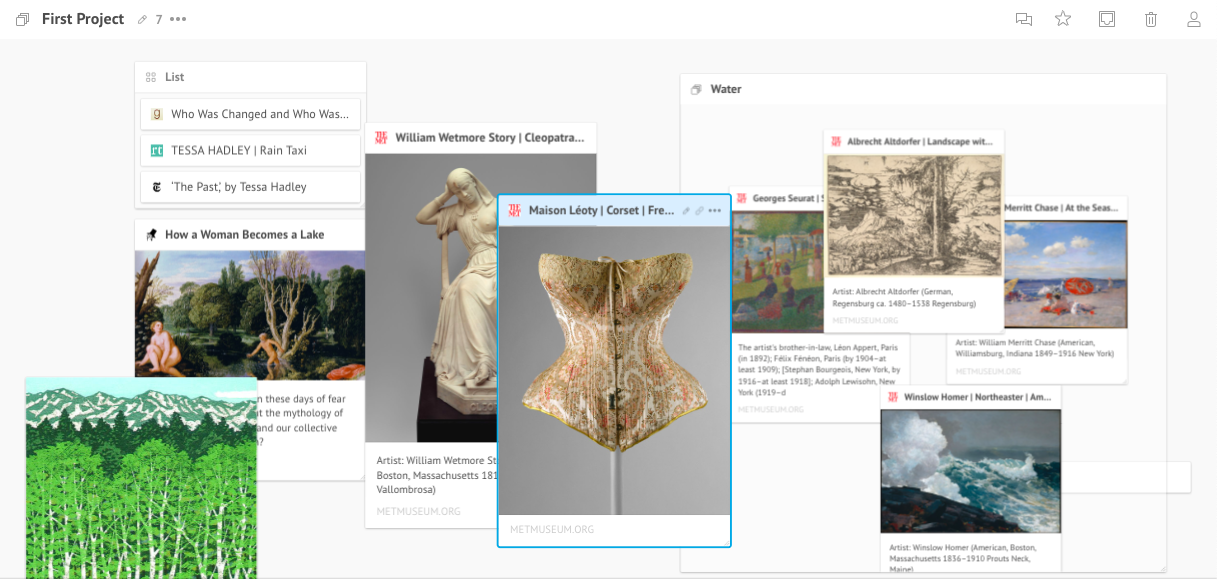

For example, if you’re working on a speech or a presentation, you could fill your canvas with thumbnail links of your subject matter. You could then attach other links (like particularly apt comments or tweets or relevant op-eds), other images (like a grabs from previous presentations), and text-based responses (like lists of audience questions) onto the images themselves.

This is helpful, and in some surprisingly deep ways. If you’re looking to repurpose or refresh a project, Webjets provides an engaging format through which to envision your work. If you’re looking to gain insights or access points into stubborn questions, Webjets can help you reorganize your files in new ways (like lists, cards, folders, or mind maps). If you’re looking to collaborate with a partner or a team, Webjets lets you share your screen for pretty efficient (and frankly very fun) collaborative brainstorming sessions.

Did I need a new way to envision and brainstorm new projects? In fact, yes! My old way of brainstorming cannot even be called a “way”; it’s certainly not efficient; and it’s not at all conducive to structured collaboration. As we work on bigger, more collaborative projects at MWS, Webjets offers a narrative snapshot that is more comprehensive and more dynamic than a linear or written description.

The question of whether or not Webjets aids productivity is harder to answer. On the one hand, it will undoubtedly add to the bottomline of time spent brainstorming and collaborating. On the other hand, if it means the end result is a smarter and more creative project, then I’ll happily take it. Have you used Webjets? Tell me more.

Her book gives a comprehensive overview of professional writing and pragmatic, utterly helpful advice. While it’s an ideal reference for anyone dipping a toe into the world of professional writing, the insight and advice ripples outward to other professionals, too.

Take, for instance, Friedman’s injunction to avoid wasting someone’s time. For writers, a pitch to an unresearched editor, to an ill-chosen agent, or to an unsuitable publication is not a hail-mary strategy—it’s a waste of the reader’s time and a waste of the writer’s time.

This is the case for all types of pitch-makers. You might be pitching a report to shareholders, a book to an agent, an argument to an audience, a grant to a grantor, or a professional background to an interviewer. In each case, your aspiration should be for your audience to consider the time they spend with you and your work to be worthwhile.

You will gain their appreciation by knowing that audience not as an indistinct bulk but as a single person. Recognizing your audience as a single (and actual) person makes it easier to undertake the work of understanding their professional background, needs, and aspirations. Only then can you determine if your work (or your speech or your grant) really is a good fit. Can you give this person something they need? If yes, then you can succinctly and persuasively explain what you have to offer.

This type of reconnaissance isn’t as fuzzy as it sounds. You don’t have to divine motivations (though you may want to). You simply have to turn to Google to trace your audience’s past work and current efforts. The time you spend—no matter your pitch, no matter your audience—will always be well-spent.